Police Reform in Massachusetts – An Act Relative to Justice, Equity and Accountability in Law Enforcement in the Commonwealth (Chapter 253 of the Acts of 2020)

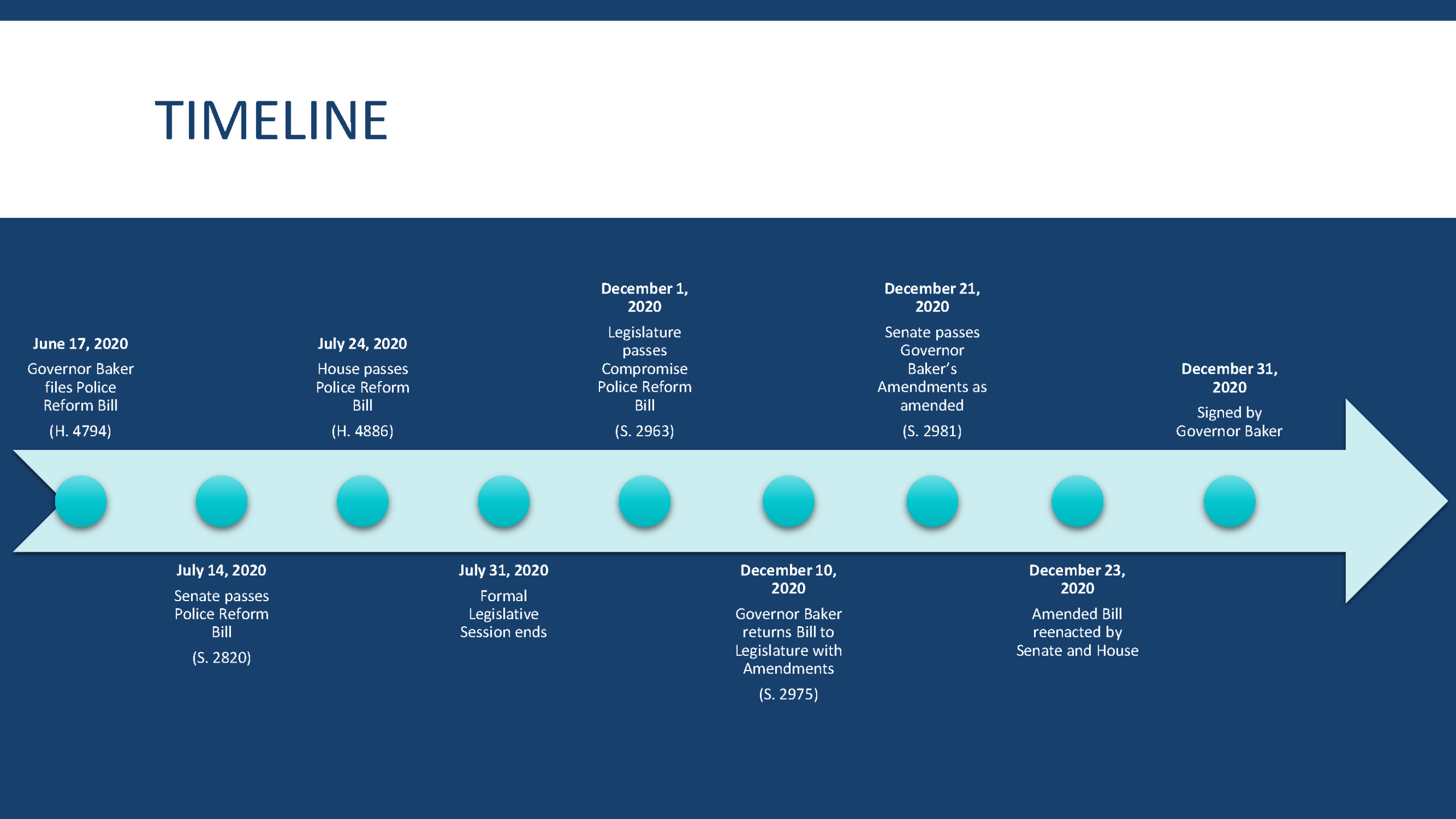

Over the summer and in the wake of the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and nationwide protests against police abuse and brutality, police reform received renewed attention on Beacon Hill. On June 7, Governor Baker unveiled a Police Reform Bill. In late July slightly differing versions of police reform bills passed in both branches. With only days to go until the formal legislative session ended on July 31, the bills headed to the House-Senate conference committee for resolution. Ultimately there was not enough time to get something done by the end of July. However, after months of behind-the-scenes negotiations, a compromise bill was unveiled and on December 1, 2020, the 128-page bill passed both houses and was sent to the Governor for review. After several days of speculation and uncertainty, Governor Baker responded with 13 pages of amendments which he stated outright needed to be accepted or he would not sign the Bill. A copy of the letter is available here. With a few modifications, the Governor’s amendments were accepted, and the resulting Bill was signed into law on, as I mentioned, on December 31, 2020.

The core of the new law is the creation of the Massachusetts Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) Commission, an independent state entity – comprised mostly of civilians – which would oversee the certification and decertification of police officers, and investigations into police misconduct.

Police unions across the Commonwealth opposed and criticized the bill. Advocates of reform were disappointed by the limited changes made to qualified immunity and compromises made around the use of facial recognition software. Attorney General Maura Healey’s Officer raised concerns about the compromise bill’s approach to no-knock warrants and in the final version changes were made to allow some additional flexibility.

The final version of the legislation is available here. The key provisions of the law are summarized below:

Creates a new Commission to Certify Massachusetts Police Officers

The bill creates the 9-member Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST) Commission to establish the minimum certification and decertification protocols for law enforcement agencies and officers. Commission members would be appointed by the Governor and Attorney General (3 appointed by Governor, 3 appointed by the AG and 3 jointly appointed by the Governor and AG), and consist of mostly civilians to include an attorney, a social worker, and a retired judge. Commissioners shall include people of color and women, “at least in such proportion as these groups exist in the commonwealth’s population as periodically determined by the state secretary….” The governor shall designate the chair of the Commission; the Commission would appoint an executive director.

The bill establishes two divisions within the Commission, the Division of Police Certification and the Division of Police Standards. The Division of Certification would be responsible for developing training standards and standardizing the certification process for law enforcement agencies and officers, while the Division of Police Standards would primarily investigate and adjudicate complaints of officer misconduct.

The Commission would serve as a civil enforcement agency responsible for certifying, restricting, revoking, or suspending certifications for law enforcement officers, agencies, and training academies. It would also maintain a public database of decertified officers, officers whose certification has been suspended and officer retraining.

- Division of Certification

The Division of Training and Certification is responsible for establishing uniform policies for certification of all law enforcement officers. Massachusetts is currently one of only a handful of states that does not have a certification or licensing process for police.

The Commission will be responsible for certifying all law enforcement agencies within the Commonwealth, and no law enforcement agency would be able to appoint or employ a law enforcement officer, unless the officer is certified. Officers who have already completed training at a law enforcement academy and have been appointed as of the effective date of the bill, will be deemed to be certified. However, going forward officers will have to periodically recertify.

The law prohibits certification of any officer who fails to meet the minimum certification standards or who is listed in the national decertification index or the database of decertified officers as maintained by the Commission.

It also establishes minimum certification standards for all law enforcement agencies and provides for the creation of agency policies regarding: use of force and use of force reporting, officer codes of conduct, officer response procedures, criminal investigation procedures, juvenile operations, internal affairs and officer complaint procedures, detainees, and collection and preservation of evidence.

NOTE: As amended, the POST Commission is NOT responsible for overseeing Police Training; the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security (EOPSS) retains its responsibility for training. This was one of the areas that Governor Baker was not willing to compromise on and was amended from the Initial Compromise Bill.

- Division of Police Standards

The Division of Police Standards is charged with investigating officer misconduct and making disciplinary recommendations to law enforcement agencies. This part of the Commission is responsible for establishing and maintaining a database for complaints about officer misconduct, and regularly monitoring the data to identify patterns of unprofessional police conduct. The database shall include information relating to an officer’s certification or decertification, arrests or convictions, disposition of internal affairs complaints and investigations, and any information relating to an officer’s prior separation from a law enforcement agency. The law amended the Public Records law so that records related to law enforcement misconduct investigations ARE NOT subject to the public records law.

Under the new law, law enforcement agencies will be required to submit copies of complaints alleging officer misconduct and other information relating to the complaint to the Commission within 2 business days of receipt. And then, upon completion of its investigation of the complaint, a law enforcement agency must report the disposition of the investigation along with any recommended disciplinary action to the Commission.

The Commission may independently initiate preliminary inquiries into the conduct of law enforcement officers upon receipt of a complaint or other credible evidence in certain situations including involvement in an officer-involved injury or death, or commission of a felony or misdemeanor, regardless of whether the officer has been arrested, charged, indicted, or convicted.

Within 30 days of initiating a preliminary inquiry, the Commission must notify the officer, the head of officer’s collective bargaining unit, and the head of an officer’s appointing agency of the inquiry.

The Commission may immediately suspend the certification of an officer who is arrested, charged, or indicted for a felony, and may also immediately suspend an officer’s certification, if it determines that the officer engaged in conduct that constitutes a felony following a preliminary inquiry.

Similarly, the Commission may, after a preliminary inquiry, suspend an officer’s certification if he is arrested or charged with a misdemeanor if it determines that the crime affects fitness to serve as a law enforcement officer. During the pendency of an inquiry, the Commission may suspend the certification of any officer if it determines that the suspension is in the best interest of the health and safety of the public.

The Commission is required to provide a hearing to an officer whose certification is suspended within 15 days. The Commission shall not institute a revocation or suspension hearing until the officer’s appointing agency has issued a final disposition, provided, however, the delay shall not exceed 1 year. At the officer’s request, such hearings may be suspended up to a year pending the appeal or arbitration of an appointing authority’s decision. Revocation or suspension proceedings or hearings, and the regulations promulgated for such proceedings and hearings shall be pursuant to chapter 30A. Any suspension issued by the Commission will remain in effect until the final decision of the Commission.

The Commission shall have the authority to revoke or suspend an officer’s certification after finding by clear and convincing evidence that the officer engaged in misconduct. The Commission also has the authority to order an officer to undergo retraining. The Commission must immediately notify the head of the agency of an officer who is decertified, suspended or ordered to undergo retraining.

Any appeal relating to the Commission’s decision to suspend or revoke a certification may be appealed pursuant to chapter 30A. However, adverse employment actions resulting from a Commission’s decision to revoke a certification may not be appealed to the Civil Service Commission.

Limited Qualified Immunity Reform

One of the more contentious areas of debate around police reform, the new law stops short of limiting Qualified Immunity for certified officers, but a police officer decertified by the Commission would lose his or her immunity. The bill would also create a special legislative commission to study the impacts of the qualified immunity doctrine on the administration of justice, including the legal and policy rationales for the doctrine.

The proposed bill creates a right to bias-free professional policing, which means decisions without consideration of a person’s race, ethnicity, sex, gender, national origin, immigration status, or other characteristics. However in the final version the definition of bias free policing was amended to allow for consideration of a person’s race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, mental or physical disability, immigration status or socioeconomic or professional level if relevant to the crime. The bill would not extend immunity to an officer who violates a person’s right to bias-free professional policing, while acting under color of law, by engaging in any conduct that would result in the officer’s decertification. There is some concern regarding the wording of the bill which states only officers who violate a person’s right to “bias-free policing” and are decertified lose their qualified immunity protections.

Reform advocates are disappointed that the bill does not remove or amend existing language in the state’s civil rights law that makes it difficult to sue a police officer for civil rights violations unless an officer interferes or attempts to interfere in an individual’s enjoyment of any state of federal law by threat, intimidation or coercion. Officers shall not be entitled to immunity from civil liability if the officer’s conduct is knowingly unlawful or objectively unreasonable, however, there is concern that an officer would have to explicitly threaten or intimidate someone for the immunity not to apply.

Use of Force, Duty to Intervene, and Mass Demonstrations

The proposed bill creates stronger use of force policies, prohibits certain actions, and requires the use of de-escalation tactics. An officer may use deadly force only if de-escalation tactics have been unsuccessful or are not feasible based on the totality of the circumstances. Use of chokehold restraints is expressly prohibited, and the bill restricts officers from firing at or into fleeing motor vehicles unless necessary to prevent imminent harm, and creates rules around the use of tear gas, dogs, and rubber bullets. The bill also creates an explicit duty to intervene and report a fellow officer if an officer witnesses a colleague using of excessive force.

- Physical Force. The proposed bill restricts an officer’s use of physical force, unless de-escalation tactics have been unsuccessful or are not feasible based on the totality of circumstances, and physical force is necessary to: effect a lawful arrest or detention, prevent escape from custody, or prevent imminent harm and the amount of force used is proportionate to the threat of imminent harm.

- Deadly Force. An officer may only use deadly force if de-escalation tactics have been unsuccessful or are not feasible based on the totality of the circumstances, and deadly force is necessary to prevent imminent harm to a person.

- Chokehold Restraints. The bill expressly prohibits the use of chokehold restraints by law enforcement officers and the discharge of firearms at or into fleeing motor vehicles, unless the discharge is necessary to prevent imminent harm and is proportional to the imminent threat.

- Duty to Intervene. Requires an officer to intervene if he or she witnesses another officer using physical force beyond that necessary or objectively reasonable in the situation based on the totality of the circumstances, unless intervening would result in harm to the officer or another identifiable person.

Mandates that an officer who witnesses the use of excessive force report it to his or her supervisor as soon as possible, but not later than the end of an officer’s shift. Law enforcement agencies must develop and implement policies for officers to report another officer’s use of excessive force without retaliation or fear of retaliation within the department.

- Mass Demonstrations. Prohibits the discharge of tear gas, use of rubber bullets, or deployment of dogs/K-9 officers to influence, control or subdue a person, unless de-escalation tactics have failed or are not feasible based on the totality of the circumstances and the use of such measures are necessary to prevent imminent harm and are proportional to the imminent threat. If any of these measures are used during crowd control, the head of the law enforcement agency is required to file a report with the Commission.

Imposes a requirement that police departments attempt in good faith to communicate with the organizers of a planned mass demonstration or protest, when the police have advance knowledge of the event. The bill requires that departments plan to avoid and de-escalate any potential conflicts stemming from the event and specifically designate an officer in charge for such plans.

No-Knock Warrants

The bill requires that no-knock warrants be issued by a judge and only upon a showing of probable cause that the officers’ lives or the lives of others would be endangered if officers were required to knock and announce before executing a warrant, and an attestation that there is no reason to believe that minor children or adults over 65 are in the home unless there is incredible risk of imminent harm to a child or person over the age of 65 (i.e., kidnapping or hostage situation of a child or person over 65).

Civil Service System Review

The Civil Service system is the system that most departments across the state use to hire and promote police officers. The proposed bill establishes a special legislative commission to study and examine civil service laws, personnel administration rules, hiring procedures and bylaws for municipalities not subject to civil service laws, and state police hiring practices. The commission is tasked making recommendations to improve diversity, transparency, and representation of the community in the recruitment, hiring, and training for civil service employees, municipalities not subject to civil service, and the Massachusetts State Police.

The bill also calls for the legislative commission to study the feasibility of creating a statewide diversity office and diversity officers for each municipality with a police or fire department.

Body Worn Camera Task Force

Directs the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security to establish a body camera task force. The task force will propose regulations to establish a uniform code for procurement and use of body cameras for law enforcement agencies in the Commonwealth.

The task force, which will consist of 25 members, must file a report and adopt draft regulations for law enforcement agencies on or before July 31, 2022. The draft regulations must include: training on use of body cameras; standards for the types of encounters and situations when a body camera will be activated and when recording may be discontinued, and requirements for retention and storage of body camera footage.

Facial Recognition

Another area of significant debate was the use of Facial Recognition Technology. The initial version of the bill essentially banned use of this technology in the Commonwealth except for by the Registry of Motor Vehicles and set up a process whereby law enforcement agencies could request and receive access to the use of this technology through the RMV. The final version of the Bill maintains some limited on the use of this technology but expends the use and allows law enforcement agencies to work with the state police and FBI, as well as the RMV. The new law also creates a commission to study the use of this technology in the state.

The Governor and Attorney General Maura Healey’s offices had expressed concern regarding the ban on the use of facial recognition software by the government, and in his amendments the Governor instead advocated for the creation of a special commission to study the use of such technology prior to implementing any ban. Boston already bans the use of facial recognition technology. The Boston City Council voted to ban its use this summer, making it the second largest community in the world to do so (San Francisco is the largest). Several other Massachusetts communities also have a ban including: Somerville, Brookline, Northampton, Springfield and Cambridge.

School Resource Officers (SROs)

Authorizes the Commission to issue a specialized certification for officers acting as SROs.

The bill establishes a special commission to review and recommend changes, as appropriate, to the model school resource officer memorandum of understanding. The model memorandum must include: the mission statement, goals and objectives of the SRO program, roles and responsibilities of the SRO, police department and school; process for selecting school resource officers; procedures for incorporating SRO’s into the school environment; information sharing between SRO’s and school staff; training for SRO’s; and the organizational structure of the SRO program, including supervision of SROs.

Directs the chief of police, in consultation with the school superintendent, to establish operating procedures for the SRO with respect to the following: use of force, arrest and citation authority on school property; chain of command for the SRO; performance evaluation standards; and a statement and description of students’ legal rights relating to searching and questioning of students.

Allows the superintendent to make a request to the chief of police for the appointment of an SRO, rather than mandating that a municipality or school district employ an SRO.

Forbids SROs and school department personnel from disclosing certain student information to law enforcement officials, except where written consent is obtained from the student, parent or guardian, or to comply with a court order or subpoena. The restrictions on information sharing also do not apply for the purposes of the mandatory reporting of abuse or neglect pursuant to M.G.L. c. 119, § 51A.

Ban on Racial Profiling

The bill outlaws a law enforcement agency from engaging in racial profiling and authorizes the Attorney General to enforce this ban by seeking injunctive or other equitable relief.

Submitting False Timesheets

Any officer who knowingly submits a fraudulent timesheet, may be punished by a fine of three times the amount of the fraudulent wages received or up to 2 years of imprisonment.

Massachusetts State Police Reform

The bill includes changes to the state police incited by the overtime fraud scandal, including the provisions on submitting false timesheets and requiring the training for state police be approved by the POST Commission and a requirement that state police officers be certified by the Massachusetts POST Commission. In addition the bill would allow the appointment of a colonel of the state police from outside the state police, and authorizes the colonel of the state police to establish a cadet program.

Expungement

Expands eligibility for record expungement from one criminal or juvenile record to two. Also allows multiple charges stemming from the same situation to be treated as one offense for purposes of expungement.

Other

The bill also prohibits sexual intercourse with a person in custody (making it a violation of the rape statute), addresses data collection of law enforcement related injuries and deaths and provides that records related to law enforcement misconduct are subject to the public records law.

SPECIAL COMMISSIONS CREATED BY BILL

Body Camera Taskforce

Community Policing and Behavioral Health Advisory Council

Permanent commission of the status of African Americans

Permanent commission of the status of Latinos and Latinas

Permanent commission on the status of people with disabilities

Permanent commission on the status of Black men and boys

Commission to study the feasibility of establishing a statewide law enforcement officer cadet program

Commission on corrections officer training and certification

Commission to investigate and study the benefits and costs of consolidating existing municipal police training committee training academies

Commission on emergency hospitalizations